Who do you think you are? Doing, being and becoming a pragmatic researcher-practitioner – a personal reflection.

This chat will be hosted by Sarah McGinley @sarah_lou2222 and Rachel Dadswell @DrRachOT1

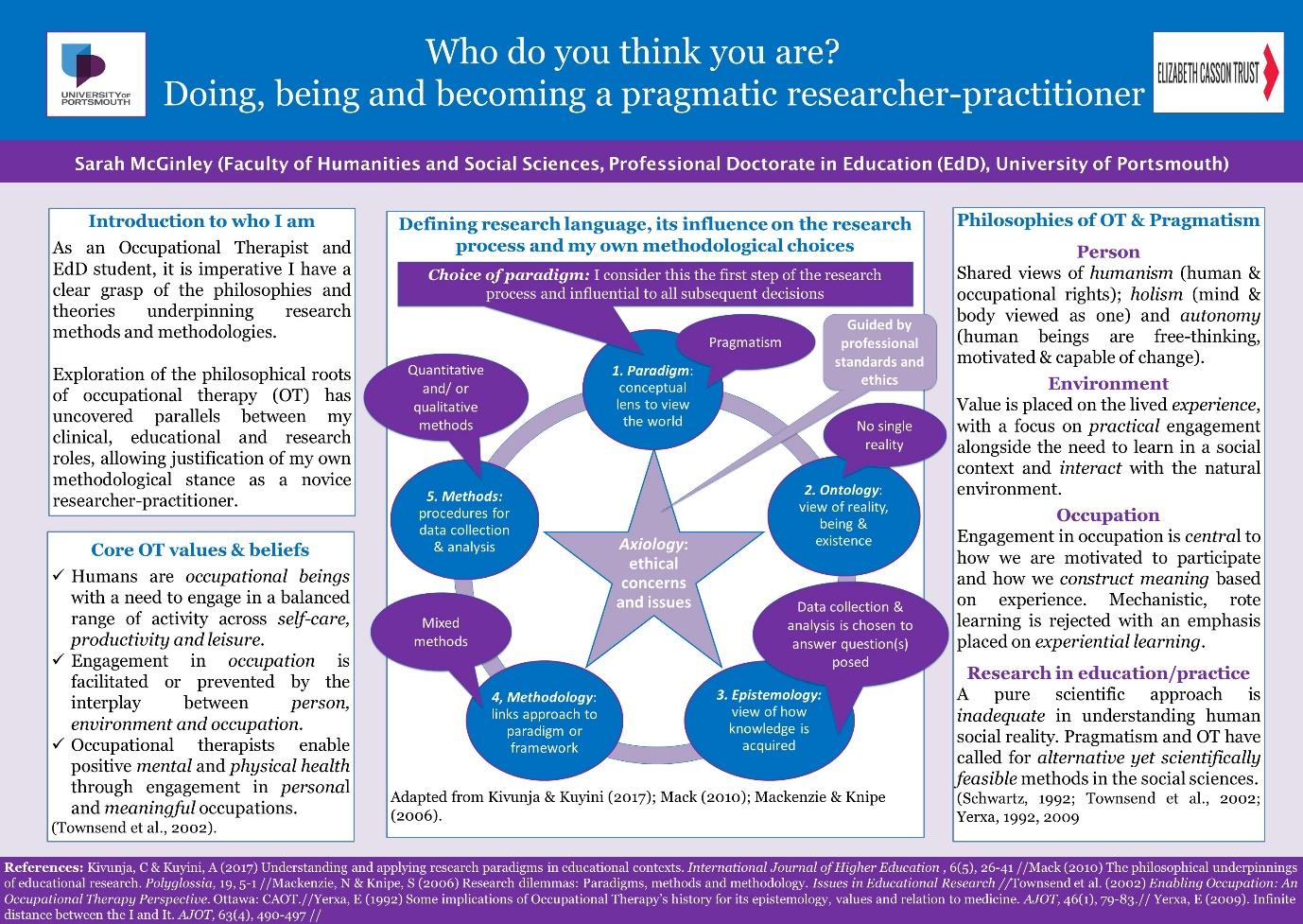

As occupational therapy students and therapists we are all aware of our personal and professional responsibility to acknowledge and examine our own values, beliefs, attitudes, assumptions, decisions and actions across clinical, educational and research contexts (Royal College of Occupational Therapists, 2021; Cunliffe 2016). Having worked in clinical practice for several decades between us, Rachel and I felt secure and firmly rooted in what we see as the underpinning philosophy of OT; the human right to engage in meaningful occupations to maintain and sustain positive physical and mental well-being (Townsend et al., 2002). However, when we entered the realms of education and research as novice researchers, we were challenged to consider our assumptions about how knowledge is generated and utilised, as well as our perception of what reality, being and existence is (Kinsella & Whiteford, 2009; Mack, 2010). Having never explicitly been asked to consider our own philosophical assumptions in clinical practice, this opened up a whole new world that was unfamiliar, overwhelming and somewhat intimidating. Words such as epistemology, ontology and paradigmatic thinking were new to us (see attached poster for definitions of research language) and took us on a journey of ‘doing, being and becoming’ researcher-practitioners (Wilcock, 1998).

The philosophical roots of OT demonstrate justified parallels with several philosophical paradigms (a lens through which we view the world). Using the poster as an illustration, we offer just one example of how the paradigm of pragmatism has helped us to understand who we are, what we do and how we view the world. Pragmatists argue that social reality cannot be understood through a singular world-view, suggesting a pluralistic approach that adopts mixed methods as a means of understanding human behaviour, beliefs and resultant consequences is needed (Kivunja & Kuyini, 2017). This quote from one of the founding educational philosophers of pragmatism – “it is through what we do in and with the world that we read its meaning and measure its value” (Dewey, 1959, p19) – demonstrates how pragmatism offers a shared view of the world that we feel aligns well with the core concepts of OT:

- Person – shared views of humanism, holism and autonomy.

- Environment – values the lived experience, focuses on practical engagement and the need to learn in a social context and interact with the natural environment.

- Occupation – emphasises experiential learning and links occupation to meaningful and active participation.

- Research in education and practice – rejects a pure scientific approach and calls for alternative, yet scientifically feasible methods in the social sciences.

(Schwartz, 1992; Townsend et al, 2002; Yerxa, 1992, 2009)

Literature suggests the profession struggles to succinctly describe OT in a uniform way, possibly connected to a lack of agreement around what constitutes its core values and connection with the founding philosophers (Kinsella & Whiteford, 2009; Yerxa, 1992). This is unsurprising if as students, clinicians, educators and/or researchers we are not routinely encouraged to understand or make explicit our own philosophical assumptions at every stage of our personal and professional development. If we are to be understood by registrants and the wider society, we feel it is imperative that philosophical language and paradigmatic thinking is introduced and made accessible to us as students, with critical reflection encouraged throughout all career pathways. We would love to know your views on this…….

Question 1: What do you understand by the term philosophical assumptions (and why is it important to consider them)?

Question 2: Do you feel comfortable debating the philosophies that underpin our profession? If not, why not?

Question 3: Have you ever been encouraged to consider your own philosophical position in practice, education or research?

Question 4: Can you share with us your philosophical position and how or why you came to this point?

Question 5: What would encourage you to explore your philosophical position in practice, education or research?

Question 6: Has your philosophical position changed or evolved over time? If so, how?

References:

Royal College of Occupational Therapists. (2021). Professional standards for occupational therapy practice, conduct and ethics. London: RCOT www.rcot.co.uk/publications/professional-standards-occupational-therapy-practice-conduct-and-ethics

Cunliffe, A. L. (2016). “On Becoming a Critically Reflexive Practitioner” Redux: What Does It Mean to Be Reflexive? Journal of Management Education, 40(6), 740–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562916668919

Dewey, J. (1959). The School and Society (4th editio). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Kinsella, E. A., & Whiteford, G. E. (2009). Knowledge generation and utilisation in occupational therapy : Towards epistemic reflexivity. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 56, 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00726.x

Kivunja, C., & Kuyini, A. B. (2017). Understanding and Applying Research Paradigms in Educational Contexts. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(5), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n5p26

Mack, L. (2010). The Philosophical Underpinnings of Educational Research. Polyglossia, 19, 5–11.

Schwartz, K. B. (1992). Occupational Therapy and education: A shared vision. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(1), 12–18.

Townsend, E., Stanton, S., Law, M., Polatajko, H., Baptiste, S., Thompson-Franson, T., … Campanile, L. (2002). Enabling Occupation: An Occupational Therapy Perspective (Revised Ed). Ottawa: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists.

Wilcock, A. (1998). Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(5), 248–256.Yerxa, E. J. (1992). Some implications of Occupational Therapy’s history for its epistemology, values and relation to medicine. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(1), 79–83.

POST CHAT

The Numbers

1.960MImpressions

431Tweets

73Participants

9Avg Tweets/Hour

6Avg Tweets/Participant